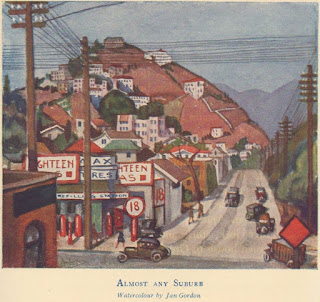

"The Dandy" - a Novel in a Nutshell by Jan Gordon, 1915

"The Sketch" of Wednesday 31st March 1915 contains a "Novel In A Nutshell" by Jan Gordon. This was written before his February departure for Serbia to serve with Dr. James Berry. I had not come across this before.

THE DANDY. By JAN GORDON.

THE infernal drumming of guns, which had died down at night fall, broke out again with the glimmer of the new dawn: gun-smoke smeared dirty finger-marks across the purity of the reddening sky, and, in the growing light, the mountain-tops seemed all afire, as though their very stones were smouldering. In the gloomy valleys, bursting shrapnel spotted the forests with sudden transient growths, like gigantic dandelion-heads, instantly dissipated by the morning breeze.

Crouching in a ditch which had been their shelter during the night, the piou-pious waited tensely. Marchand, the Lieutenant, a few paces to the rear, leaned on his sword, glancing backward from time to time at the cannon-smoke which drifted slowly up behind him. The concentrated immobility of the troop seemed to create a strange oasis of silence in the devil's racket of the cannonade. In the clear air above, two aeroplanes manoeuvred in large solemn spirals, strangely indifferent and aloof, though now and again a shrapnel suddenly splashed in the blue beneath them.

The fog of the cannon-smoke reached the soldiers, and they moved forward under its cover, coughing and spluttering in the reek, while the German shells, which had found the range at last, burst in flashes all round the advancing troop.

As the shard flipped amongst them, or when a shell buried itself at their feet without exploding, the piou-pious roared with laughter. Marchand, old soldier risen from the ranks, cursed and swore continually, searching his large vocabulary for exotic expressions obscene jests flickered up and down the line, and the men flung personal remarks at each other. "Eh, Snoutie, take your nose out of the way of that splinter." Or, "This '11 shorten the Long-un a bit if he ain't careful."

Now and then some man cried Touché," and dropped sprawling on the ground others fell silently with a queer twisting motion. "Phut, Phut," went the shells overhead and one, bursting after it had penetrated the earth, kicked up huge clouds of dust which settled heavily on some of the soldiers.

"Eh, eh," they cried, "you 'd think we 'd joined the baker's brigade."

One of the men pulled a small silver-backed clothes-brush from his pocket, and, still marching on, began to brush the dust from his coat.

"Hell!" cried the Lieutenant. "Here 's the Dandy cleaning up for his funeral."

The young man turned at the jibe, adjusted a monocle which hung from his neck by a black ribbon, and stared at the old soldier superciliously from head to foot.

"Keep your cursed window-pane off me," shouted the Lieu tenant, "or I'll crack your skull."

Capuchin, the Corporal, joined in -

"Eh, Dandy, it 's the Germans will twist your moustache l they '11 curl your hair for you, my beauty-boy ; they'll brush your jacket."

The Dandy smiled, shrugged his shoulders, and, with the monocle fixed in his eye, marched on, still brushing the dust from the lapels of his coat. The breeze, blowing sluggishly, carried the smoke along the ground, and the heavy, stinking fumes swirled about the men as they climbed steadily up-hill. The German gunners lost the range once more, and their shells burst and popped harmlessly in the French rear. Occasionally the soldiers knelt, firing unaimed volleys into the eddying smoke.

Stray German bullets twanged off the stones, growing more and more numerous, till they sang about the French like a pest of angry bees. Men were falling fast when Marchand, opening his lungs to their fullest extent, bellowed -

"Chargez, mes enfants ! Oh, charge, you d__ d recruities !"

The bugles sounded and, roaring an echo to his shout, the line of men plunged upwards. In the yellow fog their bayonets flickered like tongues of flame. Marchand, springing between Stumpy and the Long-un, raced to the head of the troop, waving his sword in strange diagrams of wrath, and shouting like a costermonger. Capuchin suddenly stumbled and fell on his knees, shrieking "Sacré ! Sacré ! Sacré !" - one hand clawing at his chest.

Untouched by the hail which had burst around him, the Dandy charged upwards, still gripping his monocle; beneath a daintily trimmed moustache his teeth were set in a wide white grin.

Nothing could stop that furious charge yelling with the lust to kill, the French hurled themselves on the enemy. Marchand, at the head of his troop, sabred a yellow-haired gunner who was grinding a stream of death on to them from a machine-gun but the Lieutenant staggered and fell in his turn, pierced by a bayonet.

The Dandy, sweating with berserk rage, stabbed the slayer, and sprang across the corpses. The French drove slowly up-hill, ducking and lunging in the smoke like fiends stoking the fires of hell. Up up, across a road, gleaming white in the dim sunlight, where two German ammunition-carts lay, wheels uppermost, in a ditch. Up ... up....

Cries of German reinforcements came filtering through the fog; the pressure grew heavy from above; the attack wavered, halted, and then began to back downhill... Across the gleaming road, now mottled with patches of red, and covered with still forms... across the trenches where the dead sprawled in uncouth attitudes...

The French retreated slowly, giving furious resistance; but the weight of numbers overbore them. The Long-un, his cheek ripped open by a bayonet-thrust, was stabbing and firing alternately with amazing rapidity. The Dandy buried his bayonet in the chest of a gigantic officer, and, in withdrawing it, broke the steel off at the haft. A German, using his rifle as a club, struck him down sideways...

The cries and bellowing of the counter-attack passed slowly down the slopes, and shadowy Germans, hundreds upon hundreds, pushed towards the fight.

All the long day the battle roared, swaying about the hillside I dead and wounded lay or writhed with distorted gestures, and rifles, knapsacks, and haversacks strewed the ground between them, all scattered as if some wilful child were destroying playthings.

The Dandy, disentangling himself from a dead man who lay over him, sat up, gently rubbed a large bruise, and smiled wryly finding his monocle still unbroken and hanging to its black ribbon, he screwed it into his eye.

He plunged his face into a cooling stream further down the hill it would be running red like wine, but here was still pure and limpid. The Dandy extracted a cake of soap, a neat aluminium shaving-set, and a good double mirror from his knapsack. He shaved carefully, then, lighting a cigarette, sat watching the smoke through his eye glass. Ever the huge bonfire of battle crackled and leaped on the hillside below.

"Adolphe, old chump," he murmured, this is going to strain your thinking-box. If you do the parsley act here you'll be chewing sausage for a bit, whether you like it or not. Oh, Lord, that fellow did give me a thump - head sings like a chorus at the Vaudeville. Sacré pigs!"

When the bursting shells made sudden stars in the growing dusk, and dark, ominous figures - ghouls or ambulance-bearers - moved stealthily among the dead and wounded, he climbed to his feet and scrambled away.

The cannonade ceased, but a roar still mounted from the valley below, a roar like the sound of a great city like Paris, like the Paris which was so distant and so dear to the Dandy shivering in the cold of the night. Lulu and Jane and Madeline, the lights of the Café d'Harcourt, and the gay frivolity of the Bullier - all deserted because these sacré sausage-eaters couldn't keep quiet... Ugh! how cold it was - how hungry he was getting

He stumbled back till he found a trench of dead men, methodically searched their haversacks, wolfed the hard emergency rations he found till he had stayed his hunger, and pocketed the residue.

Next day he was high up on the mountain-side, driven from his course by the necessity of avoiding capture. The wind, he saw, was now blowing the smoke directly into the French lines, and behind its cover the Germans were rapidly changing their position, swinging- across their rear, now in enormous masses, now in loose formation. Far behind the French fighting line a heliograph shone out.

Two French aeroplanes wheeled above, and presently one fell, twisting slowly about on its central axis till it crumpled into the trees. The heliograph twinkled on. The Dandy, an ex-telegraph employé, tried to read the message, but could make out nothing. "It's in cipher," he thought.

Huge clouds of dust behind the German lines marked the passage of a troop of motors. Then the Dandy realised that the second aeroplane was no longer visible. He had not seen it fall, but evidently something had happened.

Now the French were without eyes, battling sightlessly in the fog while, the other side of the curtain, the Germans were planning unwatched, concentrating overwhelming forces. The Dandy stood up, careless of discovery, beside himself with rage, shouting, "A droit, a droit." The heliograph winked as if in answer. "Ah, sacré miroir!" yelled the man. "Sacré miroir!" But he broke off short; even in saying this an idea had flashed upon him. He felt in his pocket, whistled a long uprising note, and snapped his fingers. Then he looked about him. "Not here," he muttered; "they 'd catch me here." Passing some corpses, he stripped them of their cartridge-belts, picked up a couple of rifles, and from a dead officer took a revolver and ammunition. At length, ensconced high up on the buttress of an overhanging rock, he pulled from his pocket the double shaving-mirror and wrenched the two glasses apart.

The French signalling-station poked up its poles and stays in the rear of the smoke-curtain. Near by, in an open field, four mechanics were sweating about a broken-winged aeroplane. The aviator, exhausted by a four-days' continuous battle, lay stretched on the grass, his head resting on his crossed arms. At the foot of the wire less masts was a large, caravan-like motor-wagon soldiers, some chaffing, others lying half asleep on the ground, waited round it. Sometimes one or other of them, called, would stride to the window, receive some paper, salute, mount a motor-cycle, and clatter away towards the fighting line.

Far away in the hills a spot gf light twinkled violently, disappeared, then sprang out afresh. One of the men, out of curiosity, put up his field-glasses. "Hello," he said, "someone 's trying to signal. They 're saying S.O.S. S.O.S.," and then "Français, hello la bas." The others turned, looked for a moment, and scoffed at the notion. "But it is so," insisted the man. "They're signalling S.O.S. S.O.S. Français, hello là bas.' It 's perfectly clear. Here, Charcot, get out your heliograph and answer him. Let 's see what the d__d German is playing at."

The man sitting at the heliograph adjusted his mirrors and snapped out a reply. The distant spot twinkled in answer. Charcot flickered the keys. The knot of watching signallers grunted as they read the message from the far hills. Some laughed.

"May be something in it," said Charcot "he uses good Parisian argot. Send it to the Général, anyhow."

He scribbled rapidly.

All about the French fines of communication motor-cyclists buzzed like angry hornets. At a cross-road they swirled about like a whirlpool, coming, going, crossing and re-crossing in a never-ending stream. There, at this centre, was a huge steel car, and within the car General Sansot, his eyes drawn to thin lines from lack of sleep, his eyebrows and mouth fixed in never-wavering parallels, glowered over a map.

He looked up suddenly. "That aeroplane," he shouted. "Send another messenger."

"Mon Général," said an officer, "word has just arrived. The aeroplane cannot be repaired in less than three or four hours." Another officer approached and saluted.

Message from the signal-station, mon Général," he said, handing a despatch.

That spot of light away on the hillside had caused Charcot to write the following

"To General commanding. Have picked up a heliograph message in French from the hills behind the enemy's lines. Herewith append message received -

"(1) 'S.O.S. S.O.S. Franqais. Hello la bas.' This is repeated many times. On our inquiring the identity of the signaller, we received the following -

"(2) Private Laporte, nicknamed the Dandy, No. 47259, 13th Regiment of the Line, ex-telegraph clerk was stunned by the Bosches when attacking; have recovered, and am now in safety am using pocket-mirror as helio. Can see everything. Important concentration in German lines to north of the yellow hill. Masses of machine-gun motors will send further information when developed. End.'

"Message much interlarded with Parisian argot of a complicated nature. Should judge signaller to be French. - Charcot."

General Sansot turned to an orderly -

"Send a cyclist to the 13th. Bring back a corporal on the carrier. Full speed."

The little spot on the hillside twinkled on. Around Charcot the knot of men stared through their field-glasses, muttering in undertones.

"Noticed that both aeroplanes had been shot down. German concentration on the left seems to be weakening the centre, but this is defended by a strong battery of artillery a little to the rear. Any troops advancing on the centre would be murderously cut up. Look out."

General Sansot, after reading the second message, turned suddenly.

At the door of Ins car a soldier saluted. Two red-rimmed eyes glared in his filthy face, his clothes were in rags, and a dark, caked wound followed the line of his cheek-bone.

"Your name?" said Sansot.

"Long-un, mon Général," stammered the man - "that is to say, Bollot, of the 13th."

"Your rank?"

"Acting-Lieutenant."

Ah The General glanced at the man's sleeve. "Who promoted you?"

"Death, mon Général. All the officers were killed in the attack."

"Where is Laporte, of your regiment?"

"Missing killed or wounded up on the hill yonder. Just as we turned to retreat I was at his side when he was struck down."

"Is he an honest and brave man? Would he sell us to the Germans?"

"Never, never. He killed three Bosches at my side. We called him the Dandy because he wore an eyeglass and used scent but he was a good chap underneath. Voyez-vous the man snapped his fingers he was in the front rank, and killed the Bosche who downed our Lieutenant."

"Give me the names of two of his cronies," said the General, and their nicknames. "That will test him. Thank you. Now return to your regiment."

The heliograph twinkled like a star on the hills. In the field by the signal-station the mechanics hammered the damaged aeroplane. The aviator was asleep, lying on his back, and the sun shone on his reddened face.

"The sausage-fiends are going to attack me," read Charcot.

"I have two rifles and two revolvers, and am in an impregnable situation. Will continue message when I have killed them all." Charcot, staring through his glasses, thought he could see flashes of flame where the little star had shone, but it was too distant for any certainty."

After an interminable interval, Laporte signalled again.

"I have wiped them out, but have very little ammunition left in case of a second attack. I continue to give detailed accounts of the German movements."

Later, when the great concentration had failed and broken in an assault on the strengthened French front, General Sansot signalled congratulations. It was strange sending these messages of warm appreciation to a mere speck of light miles away.

But Laporte answered Thank you, thank you, mon Général." Then, The Germans are going to attack me again. When my ammunition gives out I shall take to the bayonet. They can't stand being tickled under the ribs."

The spot of light steadied once again, then broke out -

"That is all. Ammunition finished. They are climbing nearer - good-bye. .. Viv ..." It broke off abruptly.

Charcot could imagine the lonely figure, stabbing, stabbing, over the edge of his entrenchments and the assailants swarming up and over

The distant heliograph flashed vividly, once into nothingness. General Sansot, reading the unfinished message, solemnly touched his gold-laced cap and turned to the men-

Messieurs, he said, we salute a hero." Then, looking towards the smoking frontier, "Qui vit quand même."

With a roar, the officers and messengers gathered about him, taking up Laporte's message where it had ceased -

"La France!"

Like an embodiment of the shout, the aeroplane soared up against the sky.

THE END.

THE DANDY. By JAN GORDON.

THE infernal drumming of guns, which had died down at night fall, broke out again with the glimmer of the new dawn: gun-smoke smeared dirty finger-marks across the purity of the reddening sky, and, in the growing light, the mountain-tops seemed all afire, as though their very stones were smouldering. In the gloomy valleys, bursting shrapnel spotted the forests with sudden transient growths, like gigantic dandelion-heads, instantly dissipated by the morning breeze.

Crouching in a ditch which had been their shelter during the night, the piou-pious waited tensely. Marchand, the Lieutenant, a few paces to the rear, leaned on his sword, glancing backward from time to time at the cannon-smoke which drifted slowly up behind him. The concentrated immobility of the troop seemed to create a strange oasis of silence in the devil's racket of the cannonade. In the clear air above, two aeroplanes manoeuvred in large solemn spirals, strangely indifferent and aloof, though now and again a shrapnel suddenly splashed in the blue beneath them.

The fog of the cannon-smoke reached the soldiers, and they moved forward under its cover, coughing and spluttering in the reek, while the German shells, which had found the range at last, burst in flashes all round the advancing troop.

As the shard flipped amongst them, or when a shell buried itself at their feet without exploding, the piou-pious roared with laughter. Marchand, old soldier risen from the ranks, cursed and swore continually, searching his large vocabulary for exotic expressions obscene jests flickered up and down the line, and the men flung personal remarks at each other. "Eh, Snoutie, take your nose out of the way of that splinter." Or, "This '11 shorten the Long-un a bit if he ain't careful."

Now and then some man cried Touché," and dropped sprawling on the ground others fell silently with a queer twisting motion. "Phut, Phut," went the shells overhead and one, bursting after it had penetrated the earth, kicked up huge clouds of dust which settled heavily on some of the soldiers.

"Eh, eh," they cried, "you 'd think we 'd joined the baker's brigade."

One of the men pulled a small silver-backed clothes-brush from his pocket, and, still marching on, began to brush the dust from his coat.

"Hell!" cried the Lieutenant. "Here 's the Dandy cleaning up for his funeral."

The young man turned at the jibe, adjusted a monocle which hung from his neck by a black ribbon, and stared at the old soldier superciliously from head to foot.

"Keep your cursed window-pane off me," shouted the Lieu tenant, "or I'll crack your skull."

Capuchin, the Corporal, joined in -

"Eh, Dandy, it 's the Germans will twist your moustache l they '11 curl your hair for you, my beauty-boy ; they'll brush your jacket."

The Dandy smiled, shrugged his shoulders, and, with the monocle fixed in his eye, marched on, still brushing the dust from the lapels of his coat. The breeze, blowing sluggishly, carried the smoke along the ground, and the heavy, stinking fumes swirled about the men as they climbed steadily up-hill. The German gunners lost the range once more, and their shells burst and popped harmlessly in the French rear. Occasionally the soldiers knelt, firing unaimed volleys into the eddying smoke.

Stray German bullets twanged off the stones, growing more and more numerous, till they sang about the French like a pest of angry bees. Men were falling fast when Marchand, opening his lungs to their fullest extent, bellowed -

"Chargez, mes enfants ! Oh, charge, you d__ d recruities !"

The bugles sounded and, roaring an echo to his shout, the line of men plunged upwards. In the yellow fog their bayonets flickered like tongues of flame. Marchand, springing between Stumpy and the Long-un, raced to the head of the troop, waving his sword in strange diagrams of wrath, and shouting like a costermonger. Capuchin suddenly stumbled and fell on his knees, shrieking "Sacré ! Sacré ! Sacré !" - one hand clawing at his chest.

Untouched by the hail which had burst around him, the Dandy charged upwards, still gripping his monocle; beneath a daintily trimmed moustache his teeth were set in a wide white grin.

Nothing could stop that furious charge yelling with the lust to kill, the French hurled themselves on the enemy. Marchand, at the head of his troop, sabred a yellow-haired gunner who was grinding a stream of death on to them from a machine-gun but the Lieutenant staggered and fell in his turn, pierced by a bayonet.

The Dandy, sweating with berserk rage, stabbed the slayer, and sprang across the corpses. The French drove slowly up-hill, ducking and lunging in the smoke like fiends stoking the fires of hell. Up up, across a road, gleaming white in the dim sunlight, where two German ammunition-carts lay, wheels uppermost, in a ditch. Up ... up....

Cries of German reinforcements came filtering through the fog; the pressure grew heavy from above; the attack wavered, halted, and then began to back downhill... Across the gleaming road, now mottled with patches of red, and covered with still forms... across the trenches where the dead sprawled in uncouth attitudes...

The French retreated slowly, giving furious resistance; but the weight of numbers overbore them. The Long-un, his cheek ripped open by a bayonet-thrust, was stabbing and firing alternately with amazing rapidity. The Dandy buried his bayonet in the chest of a gigantic officer, and, in withdrawing it, broke the steel off at the haft. A German, using his rifle as a club, struck him down sideways...

The cries and bellowing of the counter-attack passed slowly down the slopes, and shadowy Germans, hundreds upon hundreds, pushed towards the fight.

All the long day the battle roared, swaying about the hillside I dead and wounded lay or writhed with distorted gestures, and rifles, knapsacks, and haversacks strewed the ground between them, all scattered as if some wilful child were destroying playthings.

The Dandy, disentangling himself from a dead man who lay over him, sat up, gently rubbed a large bruise, and smiled wryly finding his monocle still unbroken and hanging to its black ribbon, he screwed it into his eye.

He plunged his face into a cooling stream further down the hill it would be running red like wine, but here was still pure and limpid. The Dandy extracted a cake of soap, a neat aluminium shaving-set, and a good double mirror from his knapsack. He shaved carefully, then, lighting a cigarette, sat watching the smoke through his eye glass. Ever the huge bonfire of battle crackled and leaped on the hillside below.

"Adolphe, old chump," he murmured, this is going to strain your thinking-box. If you do the parsley act here you'll be chewing sausage for a bit, whether you like it or not. Oh, Lord, that fellow did give me a thump - head sings like a chorus at the Vaudeville. Sacré pigs!"

When the bursting shells made sudden stars in the growing dusk, and dark, ominous figures - ghouls or ambulance-bearers - moved stealthily among the dead and wounded, he climbed to his feet and scrambled away.

The cannonade ceased, but a roar still mounted from the valley below, a roar like the sound of a great city like Paris, like the Paris which was so distant and so dear to the Dandy shivering in the cold of the night. Lulu and Jane and Madeline, the lights of the Café d'Harcourt, and the gay frivolity of the Bullier - all deserted because these sacré sausage-eaters couldn't keep quiet... Ugh! how cold it was - how hungry he was getting

He stumbled back till he found a trench of dead men, methodically searched their haversacks, wolfed the hard emergency rations he found till he had stayed his hunger, and pocketed the residue.

Next day he was high up on the mountain-side, driven from his course by the necessity of avoiding capture. The wind, he saw, was now blowing the smoke directly into the French lines, and behind its cover the Germans were rapidly changing their position, swinging- across their rear, now in enormous masses, now in loose formation. Far behind the French fighting line a heliograph shone out.

Two French aeroplanes wheeled above, and presently one fell, twisting slowly about on its central axis till it crumpled into the trees. The heliograph twinkled on. The Dandy, an ex-telegraph employé, tried to read the message, but could make out nothing. "It's in cipher," he thought.

Huge clouds of dust behind the German lines marked the passage of a troop of motors. Then the Dandy realised that the second aeroplane was no longer visible. He had not seen it fall, but evidently something had happened.

Now the French were without eyes, battling sightlessly in the fog while, the other side of the curtain, the Germans were planning unwatched, concentrating overwhelming forces. The Dandy stood up, careless of discovery, beside himself with rage, shouting, "A droit, a droit." The heliograph winked as if in answer. "Ah, sacré miroir!" yelled the man. "Sacré miroir!" But he broke off short; even in saying this an idea had flashed upon him. He felt in his pocket, whistled a long uprising note, and snapped his fingers. Then he looked about him. "Not here," he muttered; "they 'd catch me here." Passing some corpses, he stripped them of their cartridge-belts, picked up a couple of rifles, and from a dead officer took a revolver and ammunition. At length, ensconced high up on the buttress of an overhanging rock, he pulled from his pocket the double shaving-mirror and wrenched the two glasses apart.

The French signalling-station poked up its poles and stays in the rear of the smoke-curtain. Near by, in an open field, four mechanics were sweating about a broken-winged aeroplane. The aviator, exhausted by a four-days' continuous battle, lay stretched on the grass, his head resting on his crossed arms. At the foot of the wire less masts was a large, caravan-like motor-wagon soldiers, some chaffing, others lying half asleep on the ground, waited round it. Sometimes one or other of them, called, would stride to the window, receive some paper, salute, mount a motor-cycle, and clatter away towards the fighting line.

Far away in the hills a spot gf light twinkled violently, disappeared, then sprang out afresh. One of the men, out of curiosity, put up his field-glasses. "Hello," he said, "someone 's trying to signal. They 're saying S.O.S. S.O.S.," and then "Français, hello la bas." The others turned, looked for a moment, and scoffed at the notion. "But it is so," insisted the man. "They're signalling S.O.S. S.O.S. Français, hello là bas.' It 's perfectly clear. Here, Charcot, get out your heliograph and answer him. Let 's see what the d__d German is playing at."

The man sitting at the heliograph adjusted his mirrors and snapped out a reply. The distant spot twinkled in answer. Charcot flickered the keys. The knot of watching signallers grunted as they read the message from the far hills. Some laughed.

"May be something in it," said Charcot "he uses good Parisian argot. Send it to the Général, anyhow."

He scribbled rapidly.

All about the French fines of communication motor-cyclists buzzed like angry hornets. At a cross-road they swirled about like a whirlpool, coming, going, crossing and re-crossing in a never-ending stream. There, at this centre, was a huge steel car, and within the car General Sansot, his eyes drawn to thin lines from lack of sleep, his eyebrows and mouth fixed in never-wavering parallels, glowered over a map.

He looked up suddenly. "That aeroplane," he shouted. "Send another messenger."

"Mon Général," said an officer, "word has just arrived. The aeroplane cannot be repaired in less than three or four hours." Another officer approached and saluted.

Message from the signal-station, mon Général," he said, handing a despatch.

That spot of light away on the hillside had caused Charcot to write the following

"To General commanding. Have picked up a heliograph message in French from the hills behind the enemy's lines. Herewith append message received -

"(1) 'S.O.S. S.O.S. Franqais. Hello la bas.' This is repeated many times. On our inquiring the identity of the signaller, we received the following -

"(2) Private Laporte, nicknamed the Dandy, No. 47259, 13th Regiment of the Line, ex-telegraph clerk was stunned by the Bosches when attacking; have recovered, and am now in safety am using pocket-mirror as helio. Can see everything. Important concentration in German lines to north of the yellow hill. Masses of machine-gun motors will send further information when developed. End.'

"Message much interlarded with Parisian argot of a complicated nature. Should judge signaller to be French. - Charcot."

General Sansot turned to an orderly -

"Send a cyclist to the 13th. Bring back a corporal on the carrier. Full speed."

The little spot on the hillside twinkled on. Around Charcot the knot of men stared through their field-glasses, muttering in undertones.

"Noticed that both aeroplanes had been shot down. German concentration on the left seems to be weakening the centre, but this is defended by a strong battery of artillery a little to the rear. Any troops advancing on the centre would be murderously cut up. Look out."

General Sansot, after reading the second message, turned suddenly.

At the door of Ins car a soldier saluted. Two red-rimmed eyes glared in his filthy face, his clothes were in rags, and a dark, caked wound followed the line of his cheek-bone.

"Your name?" said Sansot.

"Long-un, mon Général," stammered the man - "that is to say, Bollot, of the 13th."

"Your rank?"

"Acting-Lieutenant."

Ah The General glanced at the man's sleeve. "Who promoted you?"

"Death, mon Général. All the officers were killed in the attack."

"Where is Laporte, of your regiment?"

"Missing killed or wounded up on the hill yonder. Just as we turned to retreat I was at his side when he was struck down."

"Is he an honest and brave man? Would he sell us to the Germans?"

"Never, never. He killed three Bosches at my side. We called him the Dandy because he wore an eyeglass and used scent but he was a good chap underneath. Voyez-vous the man snapped his fingers he was in the front rank, and killed the Bosche who downed our Lieutenant."

"Give me the names of two of his cronies," said the General, and their nicknames. "That will test him. Thank you. Now return to your regiment."

The heliograph twinkled like a star on the hills. In the field by the signal-station the mechanics hammered the damaged aeroplane. The aviator was asleep, lying on his back, and the sun shone on his reddened face.

"The sausage-fiends are going to attack me," read Charcot.

"I have two rifles and two revolvers, and am in an impregnable situation. Will continue message when I have killed them all." Charcot, staring through his glasses, thought he could see flashes of flame where the little star had shone, but it was too distant for any certainty."

After an interminable interval, Laporte signalled again.

"I have wiped them out, but have very little ammunition left in case of a second attack. I continue to give detailed accounts of the German movements."

Later, when the great concentration had failed and broken in an assault on the strengthened French front, General Sansot signalled congratulations. It was strange sending these messages of warm appreciation to a mere speck of light miles away.

But Laporte answered Thank you, thank you, mon Général." Then, The Germans are going to attack me again. When my ammunition gives out I shall take to the bayonet. They can't stand being tickled under the ribs."

The spot of light steadied once again, then broke out -

"That is all. Ammunition finished. They are climbing nearer - good-bye. .. Viv ..." It broke off abruptly.

Charcot could imagine the lonely figure, stabbing, stabbing, over the edge of his entrenchments and the assailants swarming up and over

The distant heliograph flashed vividly, once into nothingness. General Sansot, reading the unfinished message, solemnly touched his gold-laced cap and turned to the men-

Messieurs, he said, we salute a hero." Then, looking towards the smoking frontier, "Qui vit quand même."

With a roar, the officers and messengers gathered about him, taking up Laporte's message where it had ceased -

"La France!"

Like an embodiment of the shout, the aeroplane soared up against the sky.

THE END.

"Sunrise: Inverness Copse"

Comments

Post a Comment