Jan Gordon's WW1 Dazzle design for H.M.S. Southampton

Camouflage of ships in WW1

At the beginning of WW1 in 1914, Stephen King-Hall (as "Etienne"), serving on HMS Southampton, recalled, "After the big sweep we all went to Loch Ewe to coal, and here I remember noticing the battleships suddenly break out into camouflage masts and funnels. This camouflage in those days was intended to make it harder for the Germans to take ranges of our ships, which they did by a method known as the vertical angle ; for this purpose some conspicuous vertical object is required on the ship of which it is desired to know the range."

King-Hall then tells a lovely anecdote about the response to a letter sent by a camouflage officer to a merchant skipper who had protested against the "vivid splashes of green, blue, and red with which his ship was being decorated."

"DEAR SIR,- The object of camouflage is not, as you suggest, to turn your ship into an imitation of a West African parrot, a rainbow in a naval pantomime, or a 'gay woman.' The object of camouflage is rather to give the impression that your head is where your stern really is."

This camouflage design may in part have been a result of the ideas of John Graham Kerr, as outlined in his letter to Winston Churchill, 24th September 1914 ("Protective Coloration of Ships"), but according to Murphy & Bellamy (2009), there had been earlier ad hoc efforts even before these suggestions had been made.

King-Hall continues, "After various experiments it was not considered that this camouflage was of much value, and the scheme was abandoned. Later on in the war, camouflage of the whole hull was adopted, for a different reason. The object of this camouflage was to make it difficult for a submarine to tell what course the ship was steering."

In that later phase of "camouflage," HMS Southampton, the ship King-Hall had served on for the first three years of the war, was, in 1918, decorated with a dazzle scheme designed by the artist and writer Godfrey Jervis (Jan) Gordon. More on this below.

Jan Gordon in his 1918 article explained why the term "camouflage" was not appropriate for these designs and used the expression "dazzle painting." My pet cuttlefish ("Ramses") demonstrated nicely the difference between camouflage abilities and the dramatic "motion dazzle" shown to dazzle and confuse an attacker (Ramses also happened to be very good at camouflage).

The Dazzle Scheme Project

Following devastating losses of shipping to German submarines from February 1917, Norman Wilkinson, an artist who served in the Royal Naval Volunteer Reserve, proposed the concept of dazzle painting as a means of confusing the enemy submariners as to ship course and speed. Some of the products of this new programme were very similar to those of John Graham Kerr's earlier "parti-colouring" scheme of 1914-1915 (Murphy & Bellamy 2009, pg 184), but the need was great, the time was right, and Wilkinson was a naval insider, so the proposal was given the go-ahead.

The project was set up under Wilkinson's leadership in Burlington House at the Royal College of Art during September 1917. It employed artists and model makers, with female art students applying the dazzle schemes to the small wooden models, many of which are now preserved in the Imperial War Museum. The effectiveness of the "dazzle" was tested by viewing through a periscope as the models were rotated on a turntable.

Jan Gordon joined the Dazzle Scheme project on the 9th November 1917. He was eventually demobilised from 1st December 1919. In addition to Gordon, the dazzle artists included Cecil King, Stephen Spurrier, Julius Olsson, Charles William Wylie, Montague Dawson, Frank Henry Mason, Edward Wadsworth, Charles Johnson Payne, and Oswald Moser.

HMS Southampton

The Imperial War Museum holds the schematic drawings for Jan Gordon's dazzle design for HMS Southampton (images below).

The design shows many of the principles of Dazzle, including false bows and curved shapes in opposition to the curves of the ship, making the orientation of the bow unclear to observers.

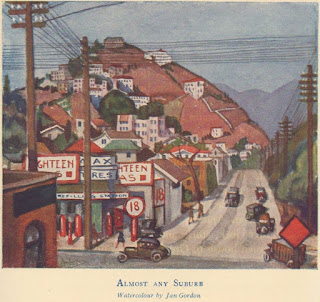

Jan Gordon and dazzle design

Legacy of the Dazzle Ships

Writing the above, I remembered my one personal encounter with a WW1 battleship - the last surviving dreadnought, USS Texas (BB-35), an extremely imposing ship in person. It gives an impression of great power and solidity. These massive ships had been envisaged to be the future of naval warfare, but the last major battle between two fleets of such ships was the Battle of Jutland in 1916. King-Hall concluded that, "Jutland, if not an overwhelming victory, was a defeat for the Germans of such a nature that they abandoned all idea of ever meeting our heavy ships again - at least such is the only conclusion possible from the evidence afforded by the extraordinarily neglected state of the machinery in the heavy ships at the time of surrender." It has been argued that the major consequence of Jutland was the refocusing of the Germans towards submarine warfare. In WW2, battleships played a more subdued role, with submarines and aircraft carriers becoming the dominant components of naval warfare.

Here below are some photographs of USS Texas from 29th December 2013.

Further reading

Dazzle Camouflage wikia page

Gordon, J.G. 1918. The Art of Dazzle-Painting. Land & Water. December 12 1918, 10-11.

Gray, D.R. Carrying Canadian Troops: The Story of RMS Olympic as a First World War Troopship, 54-70.

Jan Gordon and the Dazzle Scheme Project, Demobilisation in 1919, November 08, 2020

King-Hall, Stephen, as "Etienne." 1919. A Naval Lieutenant 1914-1918. Methuen & Co. LTD, 36 Essex Street W.C. London, 260 pp.

Comments

Post a Comment