Mr. Brown's Brigand by Jan Gordon 1923

Blackwoods Magazine for March 1923 (pages 60-82) has a story by Jan Gordon called "Mr. Brown's Brigand." Gordon makes abundant use of his experiences in Paris and Serbia and alludes to common themes of his - personal freedom and the trials and tribulations of artists. It's a long and laboured tale.

It begins with John Brown the painter entering the café Rotonde, famous and popular haunt of artists of the time. Brown's extravagant persona is described as a new phenomenon, "Le Roi Charles." He had a high-pitched drawling super-Oxford accent, in general appearance "a sort of fair-haired, anaemic, modern translation of one of Vandyke's posed portraits."

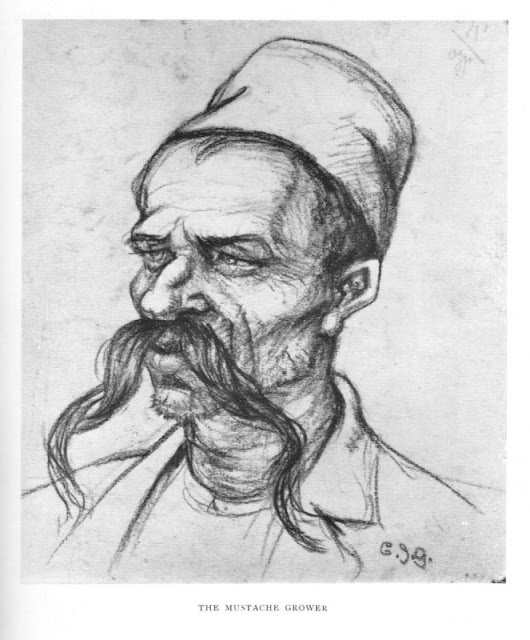

Brown was followed by a "huge companion" met in Serbia and staying with him in Paris. He was dressed in a coarse overcoat and a pointed sheepskin cap. He had a dark face "carved out into muscular shapes, deep-set morose eyes, and a long black moustache."

Jan Gordon had first met John Brown during the 2015 Serbian retreat, at Raska, a small village at "what was once the frontier of Serbia and of the old Turkish sanjak of Novi-Bazaar." Gordon and his companions had reached this spot "after a three days' toil along the valley of Bear, surrounded by the fleeing population of Serbia, and by the disordered remnants of the retreating Serbian armies." Brown had arrived there by the same route, but driven in a Moto-lorry. "The place looked like a convocation of the dirtiest gipsies one can picture. Even the staff officers were caked in mud, their black overcoats often torn and always soiled."

Gordon had gone to the Commander's office to get bread ("never an easy task") and found the Englishman Brown already there waiting. "He was dressed in the semi-officer's rig which makes the Red Cross volunteer orderly, but was so dapper, so spick, and so - yes - dainty, that I received almost a shock." Gordon found his "resplendent cleanliness" out of place in the surroundings, "like a splash of whitewash upon a solid old master." Nonetheless, "with a drawling nonchalant persistence he broke down the bureaucratic reluctance of officials to step an inch beyond their explicit orders," securing the bread and finding an Austrian prisoner to transport it in a cart.

Gordon had not seen Brown in the seven years since. "Brown's hand, like a tentacle, had an unexpected muscularity beneath it." "Fancy meeting you here," he drawled.

He indicated his Serbian friend Hussein Luković, "Brigand by profession. No work here, of course. Too much competition." He ordered milk for himself and American grog for the brigand and told Jan Gordon the story of how they came to be there.

Brown explained that he intended to be consciously alive, and he was going to be allowed to be alive. He commented that "those poor beggars that crawl to offices at six or eight and crawl home again at four or six aren't really alive. They already are entombed in oil, like a sardine."

"Before an artist is able to come to life, he must have a reasonable reputation, or call it notoriety if you prefer. This has nothing to do with his art ; most people buy pictures because of names," said Brown, "but people simply won't recollect a name like John Brown."

In pursuance of his schemes he had visited Serbia that summer, thinking he could "work up a few newspaper paragraphs from there, as well as maybe inveigle the Serbian propaganda people." He had in mind the scenery around the border between Montenegro and Serbia. He needed the permission of the police to visit the town of Chainiza and it was in the police office that he first heard of the brigands. He was granted permission, but forbidden from travelling beyond, which roused his curiosity.

An old café-keeper told him that "there were bandits all about that district ; that during the fighting—which at one time was pretty lively around there, especially during the second Serbian advance—some of the Mussulmen came upon the raw edge of fate, houses burned, families destroyed, and so on, and that several of these unattached or rather detached men had taken refuge in the mountains, called themselves comitaji, and had generally let the devil loose all down the sanjak of Novi-Bazaar."

He reached Chainiza with a couple of pack-ponies, and was delighted with the inn there, describing it as follows: "You know how those Serbian inns are shaped: four-square, with the courtyard in the centre; stables and living-rooms on the ground floor ; bedrooms upstairs, reached by an outside staircase in the yard, and a rickety balcony running all round. This courtyard was unimaginably beautiful. The walls were painted Reckitt’s blue, which contrasted with the grey old woodwork in a perfect harmony. The courtyard was inches deep in umber-coloured manure, and wine-skins always were hanging up, so that I found a combination of colours which would have enchanted Georgione." The effect was spoiled by endless rain, however.

Sheltering in the Turkish café he heard about the activity of brigands, "It was the old Robin Hood profession, Norman and Saxon translated into Serb and Turk: skin the rich to aid the poor. It was carried on chiefly by these disgruntled Moslems with a pretty vivid hatred of the conqueror. Especially were they delighted to capture a Serbian soldier." The best known of the brigands had "made a vow not to kill anybody except in self-defence, which gives one considerable license, but he used to strip the officers to the bare, and turn them loose in Adam’s vesture in the high-road. Even a general got caught once." Brown had the idea that an interview with one of the comitaji would be a scoop for the English papers, or, even better, he could be the person captured and held for ransom.

He hired a horse and set off into brigand country one morning, but was out of luck with being captured and was eventually herded back to Chainiza by an armed policeman. After making contact with a "Father Joseph-looking" individual called Ahmed he escaped the village once again, by moonlight. Regretting the long walk in the bitter cold, he began to think that "the only sensible people were clerks, who stayed at home nicely preserved in little garden-city houses,—potted men, you know, hermetically sealed from intrusive life, only with the flavouring left out." When they came to a hovel, he rolled up in his sleeping bag and slept like a dead man. After four days and nights they reached brigand headquarters.

Ahmed spoke to an old woman in what was probably Albanian and then told him that Hussein Luković wouldn’t be back till the evening, and that they could sleep. Brown was abruptly woken up by Luković in "full Albanian rig-out—white skull-cap, white coat and trousers of thick felty stuff, with tremendous black embroideries down the seams." There were four dreadfully serious men and Brown did not have a convincing story as to why he was there. He blurted out, “I want you to make me a prisoner.” "and—er—hold me up for ransom.” He "laughed in the way one does to show that one is really serious." But nobody laughed with him.

Luković's companions thought Brown was a police spy, but Luković listened to the plan that taking Brown hostage could bring his cause to an international audience and commented, “This man is no spy, he is mad.” He locked Brown in the stables for the night. After long debate during which Brown endeared himself by drawing a black and white portrait of Hussein, the plan was agreed and a ransom letter, for 300 pounds, sent to the British Consul.

Some time later, "Old Ahmed had brought back a couple of men. One was a Mussulman, very decorated and swagger-looking ; the other was clean-shaven and aristocratic, dressed in English tweeds, leather gaiters, and so on—quite up-to-date, in fact. They both saluted Hussein, and gave me a cold and reserved bow. Ahmed handed to me a letter. It was from the British Consul.

'DEAR SIR,—The gentlemen who bring this letter will arrange for your immediate release. You will please accompany them to Sarajevo, as I have made myself personally responsible for your future actions to the Serbian Government.—Yours truly,' &c."

Brown was "dragged home with a string around his neck and a tin can tied to his tail.""The Consul was obliged to give me an official wigging; but he afterwards invited me to dinner, asked for the whole yarn, and roared with laughter."

Back in England, Brown tried unsuccessfully "to drag some profit out of the adventure." He "would gladly have brought up Hussein’s wrongs before the world, for the poor old chap really has had the rough edge of fortune—family exterminated, house burned, and land confiscated ; though, of course, that is war, as we say so cheerfully, not being the victims."

He was in his studio one day when a thump on the door announced the unexpected appearance of Hussein, saying "I will stay with you and you will teach me."

Jan Gordon, sympathetic to the story, in the end becomes a kind of publicity agent for John Brown, commenting, "Indeed, I may have almost over-done my enthusiasm. Only the other day I received a curt note from a London editor asking if nothing ever happened in Paris unless Mr Brown was looking on. But my purpose has been to some extent achieved. Readers of newspapers are becoming aware of this interesting personality in the world of Art. Brown’s pictures are beginning to sell. Dealers no longer look askance at him."

Comments

Post a Comment