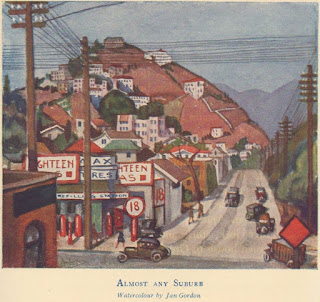

A 1920 Short Story by Jan Gordon in The Strand: Haunted Houses

In the July 1920 volume of "The Strand," Jan Gordon published a short story called "Haunted Houses," illustrated by Chas. Crombie.

The story describes an encounter between a musical country vagabond and a hungry London orphan girl in an abandoned house and muses on the meaning of freedom. The tramp concludes that "if you live in brick boxes, you pay for it, that's all. Haunted - all houses are haunted, haunted by what man could a been and wasn't, by dreams left to rot - we're all haunted - every bloomin' one."

The vagabond asks the girl about her home ("Brixton") and parents (no father and mother dead, looked after by her aunt when not drunk). He offers to teach her the flute and when she doesn't respond he sets off alone, playing a tune. She makes her decision and runs after him.

Haunted Houses by Jan GORDON

ILLUSTRATED BY CHAS. CROMBIE

The white road which curved over the first breast of the Downs did not lead to that house. Nor did the sun-faded paths nor the sheep tracks show the way, for there was no longer any road to that house, nor path nor track. Ít crouched, sullen, shunned, alone.

A gate of rusty iron trellis linked the circle of the wall, which, binding about both house and grounds, fenced them off from the generous bosom of the broad land : a crumbling wall of rotting brick and lime, seamed with many a crevice in which the rats’ eyes glinted like stars in hell's dark heaven, and whence the squeak of the field-mouse echoed faintly the plaint of that corroded gate. Within the wall dark evergreen trees stood in closed ranks, hanging their listless arms, like mourners round an open grave; dark foreign pines, a blot upon the broad still sea of interminable grass.

The setting sun could lend no warmth to those chill trees. It trailed ribbons of gay glory across the Downs—orange, yellow, and emerald, it filled the hollows with a dull lilac mist; the blackberry bushes were beaten in pure copper; even the face of the distant tramp became a grotesque, chiselled of gold, and the tragedy of his coverings a fine cloak of velvet sunbeams. The rich light fell upon those trees and was swallowed up. Only one ray, down the straight and finite avenue, Stained the front of the house and struck the fading lichens, which clung beneath the eaves, red as the seethes of blood from the lid of some damned witches' brew.

There was a child at the rust-eaten gate, hand upon the latch. She was not large, despite her thirteen years; lack of warm clothes and of nourishment had retarded her growth, had wrought her features to an elfin sharpness. Her body was lean as any wild creature's, and clad in thin cotton ripped by the briers. Her eyes were large, brilliant with weeping, and on the pale streaked mask of her face her mouth was painted purple as an Eastern houri’s with the blackberries which she had plucked to stay her hunger. A forgotten daisy-crown was on her head, a coronet awry and faded; the tangled tails of her hair, with which she had mopped the téars, hung damp against her shoulders.

A town child she was. No country girl would have dared to touch that muttering latch, nor country boy to filch one egg from the matted nests in the pines or from the swallows' earthenware beneath the eaves. A slum child, whose wits had been ground to a fine edge on the paving-stones—a slum child sent charitably upon a country holiday, to taste a health which she might not long enjoy, to see a life which she would not live, to find memories which she would never understand. That morning—a crust stolen from her village hostess's kitchen in her pocket—she had run from her town companions. Tired of exchanging taunt or blow with the village louts, unconsciously tired of so much warfare, when all her life had been warfare, she had sought a peace, taking her relish from the bramble bushes and chasing the butterfly for her sport. For some hours she had been lost.

She stood, her hand upon the latch of the gate, wondering, not at the damp decay, but at what- manner of people lived there. Her shadow, flung through the thin trellis, lay as a dark arrowhead on the viridian mosses of the sodden path. She clicked the iron and, entering, moved cautiously towards the house. The shadows of dusk entered with her, and ran upwards over the walls of that house, cooling the burning lichens to a duller red, veiling the rubies and amethysts of the broken window-panes. It was more cold in the vault of the trees than it had been on the Downs, and the damp struck through the child's poor underclothing. She shivered.

Her untamed eyes noted the broken windows, the shattered roof, and saw how on the northern corner the wall had collapsed, exposing through the serrated structure of the brickwork stained shreds of a once merry wallpaper. A-bat, chasing the evening flies, cut wild curvets against the greying sky. Once it flickered across her face and she shot out her arms, scared.

“Keep orf!" she cried, and then as she watched it, now here, now there, fantastic gambols almost an hallucination : “Crikey, it's a bird gorn barmy!”

Frightened more by the suggestion which this idea called up than by the thing itself, she hurried up the drive to the house, and, standing on the step, beat upon the door, which swung at her touch. She peered within. The door opened into a large kitchen, populated only by shadows. What light there was from the door and the large window fell upon the floor, showing the rat-holes and crevices in the worm-eaten boards, and more faintly on the great frame of the fireplace, which seemed a dark gateway— the portal of some profound mystery. All else was varying shadow—dim, indistinguishable. As the child hesitated, a rat squeaked sharply and ran across the boards. She jerked back. She was not afraid of rats, with them she had companioned in manv a city cellarage, but her nerves were now tight spanned. Loneliness in the crowd she had experienced, but the loneliness of solitude was strange, and the bat’s madness had shocked her. Recovering, she recognized friend rat by his noise, and, feeling somewhat less alone, she entered the deserted house and walked carefully to the window.

The room smelt of rot, of decay, and of death, but she did not notice this, her nostrils were inured to the yet more foetid odours of life. Here was at least shelter, here at least the loneliness was enclosed, the darkness a solid darkness which she knew, and not that dim expanse of a gloom which had no limits— height, length, breadth of infinity, negative, overpowering, which she could now see into through the window, a spacelessness and purity which seemed to hold an indistinct threat. Even the smells were comforting. But she was cold.

The afternoon weariness had wrung from her all her tears, or she would have sobbed, but her throat was closed and painful. As her eyes became more accustomed to the darkness, she began to see objects in the lost corners, here a pile of stakes, there an old sieve, a broken wheelbarrow,.and the lower part of a rickety stair which disappeared in the mottled shadows of the roof. A dark heap in the corner sent her creeping across the floor in exploration, and she found some mouldering sacks of which she began to make a bed. But before it was complete, the sound of the gate and of footsteps drove her first to the window, and thence again to the far corner, where she crouched, pulling the sacks about her to hide the dim clearness of her dress. A man was coming up the drive; she knew men, a curse at one end and a boot at the other, and, between, a stomach to hold beer for the purpose of intoxication.

The door was kicked more widely open and, framed in the square set with the dusk behind him, was the Tramp, a black, hard-edged figure, cut out as if with the nimble shears of some old silhouettist. He hesitated, peering, but the light was now insufficient, he could see nothing, so he sniffed instead like a dog.

"Stinks empty enough," he muttered ; "wonder if the floor'll blinkin' well hold.” And he put out a cautious foot.

At sunset, the Tramp, á glorious figure sitting on the far lip of the Down, had seen the house and had sucked his yellowed teeth. As the sunset died, his glory had fallen from him, the velvet changed to rags unspeakable. The gilding faded from his face, revealing the shoddy foundation; the Hesperidean apple of his throat shrivelled to a weather-dried pippin ; the flame in his eyes sank and went out behind thin slits in which simplicity and wisdom fought a never-ending battle. He sucked his degraded teeth, his narrowed eyes looking at the house, which lay in the huge cup, half-way to where upon the horizon the last embers of the sunset were cooled to grey ash.

"It’s there or nowhere," said he. ''There or nowhere; they'll pinch me if I goes back to that bloomin’ village. Cuss them farmers."

He rose and began to walk down the gentle slope, swearing amiably whenever his feet slipped upon the baked and polished grass, for he was tired. He had run some distance that day. When his feet slid he flung out an arm to balance himself and flourished in the air the corpse of a healthy cockerel which he was carrying, the fruit of his sprint and also the reason thereof.

He, too, had stood at the gate and fumbled with the latch, but he knew of the house.

“Haunted, is it? " he muttered, staring up the sullen drive. “Well, it bloomin’ well looks haunted.”

But, then, the trees were one dark n mass, ; the lichens in the blue of the dusk were an evil, purplish hue, and the aged mottled plaster

of the walls quivered with a thin phosphorescence akin to that of the evening primrose. From very far away an owl gave out intermittently its weird and solemn warning. - Things ain't always what they seem, anyhow," said the Tramp, and pulled open the iron gate.

As he set his foot on the boarded floor he stamped, and finding it firm enough took immediate possession, loosing from his shoulders the tawdry package of his worldly goods on to which he dropped the cockerel. To the child, crouching in her corner, embedded in mouldering sacks, he was now but sounds, ominous, disembodied.

A sudden streak of flame, and he had lit a match, and from the match a short end of candle, and immediately the shadows were back again, making furtive signals in the corners, playing hide-and-seek in and out of the piled stakes, and behind the wheelbarrow, as the Tramp moved here and there, a dim Diogenes. The child cowered deeper in her sackcloth, buried up to the nose, only her sharp eyes watching with a fearful enmity, with the expression of some half-cornered animal. The Tramp, slightly myopic, did not perceive her. He set the candle on the high ledge of the chimney, and began to burst in pieces some of the mouldering stakes, and with them build a fire on the hearthstone. When it was well alight he economically extinguished his petty candle, and the shadows were all set a-dancing on the walls and between the low rafters. With quick precision he dressed another stick, for a spit, ripped from the fowl entrails, which he flung through the open door into the night, and soon the bird was roasting over the clear wood fire. Its odour, mingled with the smell of the burnt feathers, filled the kitchen.

The child sniffed eagerly, with sensations similar to those she had often experienced when, empty-bellied, she had hung over the grating of some East-end cookhouse.

"Ghosts," said the Tramp to himself; " so them yokels say. All stomick and no 'ead, that's wot they is.”

He spat reflectively into the flames.

"Wish I 'ad some 'baccy—I'd make ghosts all right."

When the chicken was cooked, he wrenched it greedily apart, devouring all its detachments with gusto. Successively, legs and wings were gnawed to the bone.

The child, breaking more sticks, eager-eyed, watched him. The carcass he turned over in his hands, as if reluctant to spare, and then rising, set it on the ledge of the mantelshelf.

“Breakfass," he said ; for breakfass, ole bird,’

“you'll do better and set himself to

Then, dragging the bundle from where he had flung it by the door, he arranged it as a pillow, and lay down on the warmed hearthstone. - In ten minutes he was asleep. His slumber filled the kitchen with triumphant solo, a riotous slumber scorning the insistent quiet of that house, as his life scorned the decencies of ordered civilization.

But the child was ‘not asleep. She crouched, daisycrowned, in her sacks, like some bedraggled wood-sprite, half escaping from the earth but very awake. Sleep may be the poor man’s meal, but it becomes a sorry and an impossible substitute when rich roasted odours fill the nostrils. Dimly she could see the vague shape of the cockerel’s carcass in the upper gloom of the chimney-piece. It made her a voiceless cry far louder than the bodied sounds of the Tramp’s slumber. She hovered, wrenched by desire and by fear.

The Tramp slept on.

The rats were at the body of the chicken, edging it this way and that, and presently it thumped to the floor, but the man did not awaken. Now that the chicken lay full in the firelight it was at once more tempting and more approachable. The child cautiously pushed back the sacks and crept out, her senses intent upon the Tramp's self-advertised slumber, her desires fixed upon the food. She had seized the prize, had risen to her feet for flight, when something, perhaps that subtle aura which we all carry, and which, though imperceptible to the duller waking, has yet power to sound response from the strung senses of sleep—as the insensible wind will thrum an zolian harp— disturbed the man. The snoring stopped suddenly. The Tramp sat up, his eyes targets of amazement, his lower lip dropping.

The child, paralyzed with fear, stood motionless; in the streets she would have fled, but here under this influence she was a changed creature. So the Tramp and the girl remained for some while, each petrifying the other with the strange hypnotism of a horror-burnt gaze. The Tramp first recovered speech and action. He pushed a hand before him, motioning renunciation.

"Take it," he said, "Take it, if yer wants it."

The child, receiving, instead of blows, a gift, was yet speechless. She did not understand.

"I never in a thick voice. ’urt any of you," went on the Tramp, becoming almost plaintive, as plaintive as his weather-worn voice would permit, ‘ I never did, really. I never larfed at you even—not like others. If yer wants the chicken, take it and welcome.”

The child began to realize.

"You—you means I can 'ave it ?" eagerly.

“Welcome to it, welcome !'" cried the Tramp, wagging his head in vigorous assertion.

"An’ — an’ nuthink?”

"Now I arsts yer," expostulated the vagabond, spreading his tattered arms, ''

"''ow ' she said, yer won't boot me, nor could I? Even if I wanted ter, which I never did —no never. Not even once, s'w'elp me!"

Without more words the child set her teeth into the deep breast of the fowl greedily. The Tramp rubbed his eyes, he looked again and rubbed"once more.

“I'm dreamin’, that’s wot I am," he muttered ; '''oo ever 'eard—bloomin' fairies eatin’ chicken? It’s a dream, that's wot.”

The child continued to devour the meat.

"I'll wake up soon," said the Tramp, with hesitation, and then, doubtful whether it were dream or no: ''Yer couldn't—if it's no. offence, miss—yer couldn't git me a bit o' terbaccer, p'r'aps? No offence, of course, but for the chicken, y' know."

The child stared at him.

'" No offence, no offence," said the Tramp, hurriedly, “ only bein’ a vegetable like—I thort.”

“But,” asked the girl, t baccy from?"

“I thought," said the Tramp again, and waved his hands, ''you know—magic a bit —"

A sketched fear came into the girl's eyes.

“Is he dotty?" she thought, but aloud : "What made yer think I was a Sammon and Gluckstein.” [Salmon & Gluckstein - a British tobacconist, founded in London in 1873.]

"Sammon and Gluck!” said the Tramp, bewildered. "It’s a dream, ole man, it’s a dream." He furtively pinched himself hard.

"'Ow," he added, as the pinch took effect.

"Look 'ere," said the child, her natural urban impudence encouraged by the man's strange deference, '' 'oo are yer gittin’ at?”

“Gittin’ at?" said the man. “I wasn't. Only bein' a fairy like, I thort."

“Fairy?" said the child, “wot they has in pantermines? ’E’s dotty all right," she thought again to herself, and glanced quickly behind her to see if the path of escape were clear, `

"Pantermines!" cried the Tramp; ''but ain’t yer a fairy, with yer daisy crown an’ all?"

“Fairy ?" said the girl again; Cheese it!”

“Then,” muttered the Tramp, sinking into himself, as it were, “it is haunted. A ghost—though ghosts eatin’ chicken." His hands quivered.

'" Ghost," retorted the girl. “Ghost nix. I'm lorst, that's wot. Lorst, d' yer cop it?"

'"Lorst! " ejaculated the Tramp; “ you ain't no sperrit?”

"Wot you've been drinkin'! " said the girl. “Do I look like it?"

“Well, I'm ' said the Tramp, recovering his sang-froid, now that he had humanity and no mysterious exhalation of nature to deal with. Then, brusquely realizing too that this mere humanity was absorbing his breakfast, “ 'Ere, 'and over that chicken."

“ But you give it me,” said the girl.

“I thort ' answered the Tramp, but waved aside even the memory of the contretemps. “Lucky I don't give you an ‘iding into the bargain. And it hover, ‘Ad enuff you 'as, anyway.’

Reluctantly the child surrendered the skeleton of the chicken, for though, indeed, she had stayed the immediate qualms of her hunger, greed remained. The Tramp, rising, placed the carcass again out of reach on the high shelf of the chimney, and, ere he sat down, flung a great armful of wood upon the diminishing fire.

"Stay in the warmth if yer likes," kindly enough.

For some while there was silence, both man and child staring into the glow, while behind them on the ceiling and the walls the shadows held saraband and tarantella. The influence of the deserted house from which the Tramp by his weariness and the girl by her ignorance had been partially armoured, now reinforced by the ghostly contagion of personalities, laid hands on them, the accumulations of silence over-pressed them, driving out all thought of sleep, insinuating a thin suspicion.

At last :—

"Wasn't you afraid?" said the Tramp:

“Of you?" asked the girl. “Go on.”

"Of me—no. Of this." He waved his arm backwards.

"Of this?” asked the girl. “Were you?”

“ It was here or nowhere,” said the Tramp, “here or nowhere. And it’s cold on the Downs. Besides, it’s the yokels say it, and I don't believe them, not much—and one can always get out, if the door's open.’’ He squinted back to reassure himself.

"But," asked the' slum child, what’s there to be frightened of?”

“Ah,” said the Tramp, drawing slowly from himself with the air of one who had pondered much, ''wot's there ever to be frightened of? ’Ceptin’ perhaps bein’ chased by a dorg and bein’ bit. Police, they don't count; quod, that don't count" he said,

“ Why ?

“Wat’s an’ w'en yer die—well, you've got to some-time, so that don't count—much. Even dorgs—well, dorgs now— seems to me, speaking honest now, even dorgs 'as their uses. Teaches you you was alive, as it were, and — ànd how much man you are; you never know what a man really is til you've scampered with a dorg snappin' be'ind—not really known. No mistake. Yet—one is frightened—ortten. Y' see, l've thort ot these things sometimes.”

"I dessay," said the child, "but wot’s here?" She imitated his backward gesture.

"Here?" went on the Tramp, looking round. "Oh, well, here. lf you don't know—why, what's the use? Besides, it's only yokels' talk. Who believes farmers ? Still—to-morrow, perhaps, no use to-night— no use to-night.”

"But what is it?" persisted the child.

"Oh, well,” said the Tramp, looking suddenly again at the open door, "it is a shivery sort of place, now, isn't it? Doesnt look healthy. Eh? But, Lord! If I believed all them 'Odges say. If I wanted to believe 'em."'

He paused to ponder.

" You're town. I can see that," he continued. "So was I wonce. You dont know the country—I do. I bet there ain't one square yard in Hengland where my feet ain't patted the clod. Town now, it's all the same, it's all square and straight and hard underfoot, and bobbies at the crossings, and lights—all made out and looked atter, all hard and cornery; but the country's different. It's soft, that's wot it is, soft. You can't get its shape. You may think things, but you never know. They say there's faines, an' ghosts, an' sperrits. But you never know, not the real trooth ; anyway, they never did me no ‘arm. I'd sooner trust them than farmers, anyhow. Sometimes evenings, going down the hedgerows, I've thought things into them hedges, goblins hanging like bats in the branches and little thin foggy chaps thridding through the grass, and they always was laughing. But night-time down a havenue, specially poplars, you'd think great fellows chasing you, and footsteps behind, but nothing ever happens. And the wind in the branches sighs like there were folks shut up, but there isn't, really, you know—you think that way; that's the country."

“ And them butterflies blowin’ about like bits of coloured paper,” interrupted the child, “but artful.”

“There's nothing in towns," went on the man, pursuing his own train of thought— “doors shut like mouths that can't speak, and windows like dead eyes. But out here in the country—why, it's different. ' There's always something, something round the corner. Something great, queer maybe, but big anyhow, shadowy, hanging half up in the air like a low cloud. But that never happens neither; you go round the corner and it isn't there. lt's round the next—always round the next. But that makes no difference. Round the next corner you're a giant, ten feet high, six feet to a step—but you aren't, you know, but round the corner. Often I've wondered and wondered—what it was. Always this—wotever it is—you never catch up. Sometimes I thought it was one thing, sometimes I thought it was something else. Then I thought it was ' world without end.' Amen corner—the big bust-up. You never know what that is, not really. You don't feel that in towns—no. There's too much— too much to-morrow in towns. To-day doesn't count. And that's in houses too. Pull these houses down they do in towns, to make new red brick boxes; but here in country houses you don't know what's round the corner, or in the next room." He peered round at the mazy pattern of shadow behind him. " And then they think things. Because it's a mournful, lonely house, damp, and then things that has happened may be.”

"What things?” said the child.

"Oh," replied the man, " just things. So they say."

To change the subject, he tumbled in his pocket and pulled out a small flute.

"Wot's the good of talkin' ?'" he said. " Put some more sticks on the fire, kid, an’ we'll 'ave a toon.”

He set the instrument to his lips. He played welt. The liquid notes rippled from the wooden pipe, sometimes as falling drops of some pure translucent fluid, sometimes seeming to swell and run in iridescent chain, as go the quivering bubbles on the rapids of some mountain tarn, and to dance gambolling away through the open door into the darkness. In the firelight the Tramp's face, with its puckered lips and its weather-beaten nose, was like the carving of some old Satyr; on the stops his mahogany fingers flickered, nimble despite their graved.and swollen knuckles. The flames danced with the music, and the shadows danced with the flames.

The Tramp passed from air to air without a rest; queer airs they were, too, the girl thought, some didn’t seem to have tune at all. His fingers flew faster, trills and cascades of notes flitted into the melody, as though birds were flinging him interruptions. In the firelight the sweat glistened on the Tramp's brow.

Suddenly—silence. The music stopped in the middle of a cadenza. The Tramp's fingers hung motionless in the air, his eyes swung in his sockets, their whites gleamed out, marking his face with an expression of fear. The silence profound was broken only by the Tramp's deep-chested breathing. Slowly he straightened his eyes till he looked at the girl.

“What was that?”

"What?"

“Didn' t you hear nothing?”

“No," she said," only you.”

" Ah,” said the Tramp, after a pause, “that's the way you think things."

And he set the flute once more to his lips. But the inspiration was gone from him. He played but a few bars and then, dropping the flute, stared into the fire.

"Talking's better,” twists you up that."

"Don't you play tunes? ” asked the girl.

“You wait till you've heard them oftener," replied the Tramp; `them's the finest tunes, that you can't pick out first go oft. Them tumpty-tums—them four-cornered tunes— don't mean nothing. Drugs your mind to sleep they do; but you wait, kid, till you know them tunes, and till I play them to you out there on the highlands in the wind up to Yorkshire, or deep in a green Dorset wood.

“Them's the tunes of the country, not town tunes, no. Them town tunes come round and round, over and over again, like they live their lives. Same for everybody, rich or poor, no difference—living in boxes, dying in boxes, buried in boxes. I know; I've lived it —rich or poor don't make no difference, they wants the same things, in the same way ; they gets the same things, in the same way. The poor woman's joy in her new baby-cart is the same as the rich one’s in her moty-car ; jest the same an' lasts jest as long, till termorrer—or jest so long as they can crow over somebody else about it. They don't live: they works, or they fools so's to forget they're livin', afraid to live, that's wot it is, or livin’ to world an’ workin’ to live.

Livin’ isn’t workin’, or killin’ things, or throwin’ balls about; livin’ is seein’ things, an’ smellin’ things, an’ tastin’ things, an’—an’ makin’ things into tunes, and that-like—that’s livin’. Livin’ is running away from dorgs, an’ poachin’ rabbits—an’ you do live with a dorg behind, vivid, I can tell ver. But it’s no good saying these things to you, you can’t understand. You're a woman, an’ don't you forget it’s women make the prisons men live in.”

The child did not answer because, as the Tramp had said, she did not understand ; she still thought he was a mild lunatic.

“Yes, I know women," said the Tramp, shaking his head at the fire; ''silken women, too, I’ve known, and all alike, ‘cept one I remember. Only she was too much. It's all very well livin', but you don't want to splash ıt about. Camping out they was, three men and three women, in two tents. Younger, too, l was in them days, good-looking in a way. I used ter play to ‘em, an’ they painted me. Artists they was. One of them gals had deep eyes, that you looked down into, and risked to get drowned in. Looked into ‘em I did and played her tunes. l've torgotten them tunes now—they didn't count, just madness tunes they was. She'd a come if Id played longer to her, but I wouldn't have her. I never wanted that sort—not for long, that is. They'll take the heart from you, aye and split ıt open for red to paint their lips with. So I played to her and with her, but even she couldn't live like a real man, she had to live like a drunkard.’

He sat silent for a while, fingering his flute. Then, putting it to his lips, essayed a few tentative notes, but broke off.

“No, no," he said, ` I can t—nor want to."

But he set the pipe again to his mouth, and played the haunting wood-wind aria from "The Magic Flute." When he had finished, and the ghost of the final note had fled into the dark garden, the girl saw that a tear had run from his eye and glistened on his cheek.

"Ah," he said, flicking the tear away with a crooked finger. She wouldn't come.

"Them days," he went on, ' I lived in that town, played orchestra, I did. You know what that is ? ”

"Yes," said the girl," that black hole where the music comes from, with the red curtains."

"Near enough," said the man; * that's when I learnt that tune. That's what sent me into the country, to a man's life. Played that night after night, I did ; it was my part, solo. And it seemed so silly, sitting there, playing that tune in that stuffy, cramped hole. Blowing it into the back of the chap in front of you, when it sang of open fields and woods and breaking buds. And all you could look at was the red neck of a fat clarionet. Made me think, that tune did. Me, what had never thort before. And at night-time I'd walk back from the theatre, and all them upstairs windows alight, and that was life, lived in a box up against the sky. Happiness in a box for an hour at night ; and then in the end—another box, only a smaller one. But I never saw clear till one time, when the theatre was shut, some of us got a job for a concert in the country, and the cart broke down and we had to walk. Most of the chaps were cursing at it, which I didn't like, so I went on quick and got ahead, and lorst myself proper. Somehow I didn't mind then, it was August and warm. There was scents in the hedges and flowers in the woods. It was the first time I’d been properly alone in the country, an' I just let the concert party go, and enjoyed myself. And there were birds in the branches, so I just out with my flute and played against them, and a fine concert we had. I thought I was alone, but when I finished there was a clear clapping and a girl standing near by.

"Play some more,’ she said, ‘play some more.” The Tramp put the pipe again to his lips and plaved the air of "The Magic Flute.”

“Played her that, I did," he said. ‘ But she wanted to shut me up in a box," he went on, almost angrily, as if rebuking himself, " wanted to shut me up. A week I hung about there spending more than I could afford, and I found a new soul. Saw her and freedom together, in one picture as it were. Her in front, and Nature behind. Laughed at me, they did, when I got back, but I could afford to let 'em laugh, I had learned things. Yes, I had. Clerk in a shop she was, and not very far from me, so we came back together. And then Sundays we'd go out, to Hampstead or Hendon, or even farther sometimes, only that cost a lot., And I'd talk to her about the country and about freedom, and she agreed with her lips and with her eyes. But never in her heart, because she didn't—couldn't—understand. When spring came, I had made up my mind. I would take her by the hand, and together we would walk away, into the open country. l knew it could be done.

“Then I found she hadn't understood. All that talk with her was slop—just raving about the country because others did, and it was a nice place to holiday in. At last, because I loved her, because she loved me, too, and because she still didn't understand, I persuaded her. Got married we did, and in the fine summer away we went, me with a pack on my back and me little flute in the pocket. We took the train out of London till it was deep in the country by Epping, and then off we set. I was like a young boy just set free from school, an' like some prisoner escaped. Nothing, I thought, could touch our happiness. Couldn't it? Pah!” He paused. :

"Tight boots!" he ejaculated, and spat into the waning fire. ''Before we'd done twelve miles,” he went on, plaintively, “would you believe it? Twelve miles only, and all my happiness was running out of her eyes in tears. Proud she was of her small feet, prouder of having feet than she was of being alive. Dragged me back, them feet did, back into the red brick boxes, where I couldn't make up tunes, because they would come all square, each corner the same. Six months I stayed in them brick prisons, and me with my soul dancing out on the free lanes. Six months and our tempers gone, me dissatisfied, she knowing it, and her cursed boots, the boots that had kicked my happiness into oblivion, lying about everywhere. What I'd a done if a bloomin' uncle hadn't a died and left her some money, I dunno. Anyway, leave it he did, enough to get along on comfortable às she was used to. So I 'opped it."

“Did a bunk!" said the child, eagerly.

“Bunk it was," answered the Tramp.

“Kissed 'er after breakfast I did, walked out of the 'ouse, and never back. All the way down the street things was calling me to go back; I thought what we 'ad been, and if there might appear a kid—which there didn't—and how I might persuade her to come now—but I knew it was no go. The money stood in the way. She would want things. You can't be free if you want things; the only way you can get all you want is by wanting nothing, that's the way of 'appiness. But so soon as you want things, you may as well live in brick boxes. I wanted 'er, and there I was in a brick box. I wanted the country and my tunes; that kind of want's different. It’s all right, only I wanted 'er too. I couldn't 'ave gone back, not for 'er 'appiness nor for mine. It was a dreadful day, I remember, but when I got away from London I went shouting through the rain. I slept all night soaked in a 'ay- stack, wanting 'er bad now I was away from 'er, but I never went back. I've wanted 'er, nigh on twenty-seven years, I want 'er still, but I don't go back. Wot’s the good ?

I've known other women since, but never the same, and never it made any difference. Sometimes I've tried to comfort myself by thinkin' that what I wanted hadn't never lived at all—never was. But that didn't make any difference, for whether it was or whether it wasn't, I wanted it jest the same. And yet perhaps I've been happier because I've never really been certain, as it wore. Happier than she was maybe, because she couldn't think things and be glad about them, though about real things she was merrier than me. So I've made up tunes about her, but they were never her like this one."

He played the little melody once again. The dawn was coming up, the deserted garden outside was greying against its dark wall and trees, the salient objects in the room took on blue shapes. The fire had by now sunk into a heap of dull, reverberant ash. The Tramp shivered slightly and thrust the pipe into a pocket of one of his several coats.

“Ere,” he said, reaching up for the carcass. ''Breakfass, kiddo," and he rent it in two pieces with resolute fingers. As he was gnawing, he glanced round the mouldering kitchen.

"Haunted," he mumbled; “ they said it was haunted. All sorts of tales.”

"Tell us?" said the child.

“Not worth it," answered the Tramp. “If you live in brick boxes, you pay for it, that’s all. Haunted—all houses are haunted, haunted by what man could a been and wasn't, by dreams left to rot—we're all haunted—every bloomin' one." And he fell again on the chicken bones.

When he stood once more outside the rusty gate, he looked down at the child.

"Where's your home?" he asked.

“Brixton," she answered.

“What's father doin’?”

“’Aven't one,” she said.

"Mother? "

“Popped orf. Arntie looks after me, when she ain't jugged."

"Look ’ere,” said the Tramp, “ you 'aven't a gay life, I bet, or your face wouldn't 'ave growed that peaked way. Come along: Try this one, an’ I'll teach you to play."

“ I—I dunno," said the child, shrinking from his hand. The country stretched so broadly on every side—so huge. The Tramp still looked down on her—there was pity in his eyes.

“Well," he said," please yourself. That's your way to the village," and he pointed with his ashen stick,'' straight across there—and to Brixton.”

He turned round the wall and set off across the grass. As he went the new-risen sun flung his shadow, like a long pennant waving gentlv, over the hummocks and undulations of the Down. The girl stood now looking after him, now gazing in the direction he had indicated. She saw him set himself against the slope, walking steadily. Just as he topped the lip of the cup, he waved a good-bye, and then pulling out his pipe he began to play, and still playing disappeared from view.

The notes of "The Magic Flute” came faintly on the clear sweet morning air.

Suddenly the child came to a decision.

Crying out that he should wait for her, she ran after him.

Comments

Post a Comment